conference transcript: place-making, meaning-making, and Etel Adnan

an adamantly anti-conference graduate student attends a conference (kind of)

The writing itself is also an act of place-making: it’s the medium through which representations of home and belonging are rendered, and it’s a space of belonging in and of itself.

I’m a staunch anti-conference graduate student. I don’t enjoy the vibes. And I think that making writers speak for an audience is a special kind of cruelty.

Last week, I presented a piece of my dissertation at a conference — asynchronously. I pre-recorded my paper presentation for the organizers to broadcast during my panel time, thinking this would be perfect for me because I wouldn’t have to actually face the audience (I don’t enjoy public speaking). I was wrong. It was weird.

It was a nice push to get me to think through some tensions in my project, and I was grateful to be given the space to do so virtually, but it felt quite strange to not to be able to listen to or engage with anyone else’s work. I have no idea how my paper fit in with the rest of the panel, how the panelists interpreted the conference theme, how my presentation landed with the audience.

So, since writing and recording the presentation felt a bit like it happened in a vacuum, I thought I’d share the transcript here and shout it into a different kind of void.

My talk today orbits around a key figure in my dissertation — Lebanese American writer and artist Etel Adnan — and in particular, how she negotiates the dialectic of exile and nationalism to reimagine belonging in her writing.

In Said’s “Reflections on Exile,” he describes exile and nationalism as a dialectic, linking exile’s affective condition of loneliness and alienation to nationalistic discourses of belonging. Said explains that the affective condition of exile is so strong that it makes appealing the otherwise “bloody-minded affirmations” of nationalism. Through the dialectic, Said thus reveals the complexities of home, while highlighting the exile’s sense of intense longing, which (he argues) is precisely what makes those bloody-minded affirmations appealing to, and even ostensibly healing for, the exile.

Since the nation-state has been and persists as the pervasive organizing logic determining the conditions of exile and thus the desire for home/land, I consider the textual power of writing to be one alternative approach to finding place in the context of displacement. Writing emerges here as a form of place-making beyond the constraints of physical borders shaped by war, violence, and geopolitical conflict. For Etel Adnan, writing is not just a response to personal and collective displacement but also a way to (re)imagine and (re)create place on the page.

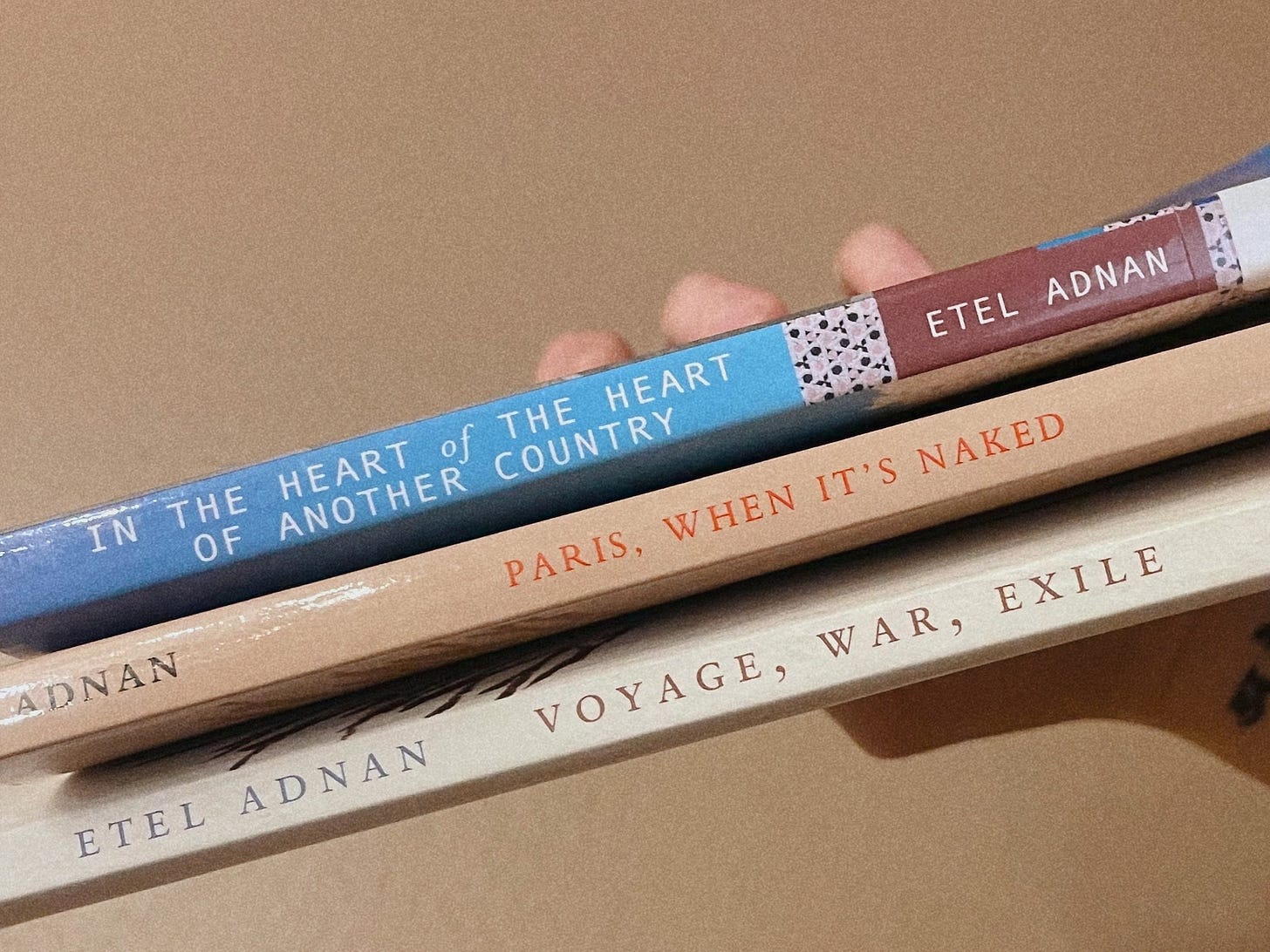

I’ve chosen two of Adnan’s texts to focus on in my presentation today — Paris, When It’s Naked (1993) and In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country (2005) — which I’ll return to in my close readings later in the talk.

Etel Adnan is generally considered a Lebanese American writer and artist because she was born and raised in Lebanon, and she ended up spending what she considers some of the most important and pivotal years of her life in the US (specifically in California). As a child in Beirut, Adnan received a classic French colonial education where she was sort of indoctrinated into the French language and therefore into a kind of discourse oriented around France as a nation-state. Arabic was forbidden from being spoken at Adnan’s school growing up, despite the school being in an Arab country, which a classic example of what Franz Fanon and Ngugi wa Thiong’o would call colonial alienation. This kind of linguistic displacement was perhaps one of the earliest experiences of exile for Adnan, and it points to the question of audience in her work.

In Voyage, War, Exile (2025), a collection of essays recently translated into English, Adnan recalls linguistic fragmentation in the context of Lebanon during World War II.

She writes:

“Little by little, Lebanon developed an intense cultural life, but this was fragmented into linguistic groups. . . . A poet or a writer never had the feeling that he or she was addressing himself or herself to the nation as a whole.” (VWE)

This linguistic fragmentation thus reflects a larger national fragmentation, which draws attention to the addressee of literature. No longer a form of national consolidation, literature both exceeds nation-state logics and also reveals a kind of limitation in terms of audience.

In the US context, she explains it this way:

“So, for my American readers my references come too often from Arab culture and history, and for my Arab readers the environment of my poetry is the American experience and the American landscape: Who would then follow me through my work?” (VWE)

The hybridity here is unsettling not only because Adnan is questioning who she’s even writing for, but also because, in the face of fragmentation, there’s the impulse to want to repair the ruptures or, recalling Said, escape into nationalistic discourses.

Nevertheless, Adnan carries one place in particular with her wherever she goes with her nomadic, hybrid sensibility, and that’s Beirut.

Critics Lisa Suhair Majaj and Amal Amireh write:

Beirut is “at once the center of Adnan’s displacement and her focal point of longing.” —Preface to Critical Essays on the Arab-American Writer and Artist Etel Adnan

So, as Majaj and Amireh write, Beirut is simultaneously the site of Adnan’s exile as well as her desire — and it’s ultimately lost to her, especially after the Lebanese Civil War.

On the destruction of Beirut, Adnan writes:

“But Beirut represents a unique case: it does not exist anymore and will not exist, I mean the Beirut I knew. It has been destroyed. . .” (VWE)

This loss of place creates a wound that can be treated through the act of remembering and recreating that place, the home/land, through art — rather than falling into the trap of nationalistic discourses, as Said writes. This kind of place-making contributes to a sense of home or belonging beyond nation-state logics, and one way this manifests for Adnan is through a certain representation of cityscapes in her writing.

For example, the site of the café — as a figure of home — features prominently in both In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country and Paris, When It’s Naked.

In a subsection titled “My House” in In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country, Adnan writes,

“I reside in cafés: they are my real homes. In Beirut my favorite one has been destroyed.” (In the Heart)

The space of the café functions as a kind of home for Adnan — a purportedly “real” home; yet it simultaneously reminds her of her actual “real” home: Beirut. Moreover, the memory of Beirut brings with it the memory of its destruction, and it’s into this kind of void that Adnan writes. The loss of her Beirut moves her to find ways to kind of fill in that gap and recreate that sense of place that’s also been lost.

The café as home also appears in Paris, When It’s Naked, where Adnan writes, of a café in Paris,

“It’s time for a break at the Café. . . It won’t give much comfort, though. Such a messy place. [. . .] It’s crowded, rather unfriendly. But it’s home, in a special way.” (Paris)

Adnan describes the café here as uncomfortable, “messy,” “unfriendly” — and yet, it’s still home to her. These descriptions attributed to the café aren’t exactly domestic or typical of what we might associate with the idea of home. They’re quite the opposite, in fact. Moreover, the association in the previous quotation between the café as home and the destruction of Beirut points to the paradoxical proximity of home to catastrophe. But to suggest that the “real” home is not Beirut but rather the café is to reaffirm the idea that the destruction of the kind of original city leads to and makes necessary the reconstruction of that which is lost both artistically and politically.

I also find Adnan’s description of hotel rooms to be quite emblematic of the exilic experience.

She writes,

“Hotel rooms hold a fascination: there’s a sense of loneliness that I sometimes experienced in them that still does haunt me. [. . .] But houses can be much worse, they can be pierced baskets from which one’s life oozes and drains into the gutters.” (In the Heart).

Hotel rooms (like cafés) are transitory spaces, but ones that still evoke a certain kind of inhabitance (unlike cafés). For example, it’s possible to still rehearse certain domestic routines in a hotel room that one might also do at home. The hotel room functions as a sort of synecdoche for the home, then, and it offers the semblance of home’s stability, despite it being an itinerant place. Then, it’s as if, for the briefest moment, Adnan is lured by the figure of home — until she remembers that “houses can be much worse.” The metaphor of the house as a basket evokes the image of the house as porous, which stands in contrast to common conceptions of home as stable and contained. So Adnan is sort of letting us know that she’s well aware of the dangers of home: the way it purports to hold a life safely but inevitably fails to do so.

It seems that Adnan both acknowledges the possibility of locating the figure of home in the city and also rejects the idea of home altogether. Adnan exposes the way home purports to (to use her metaphor) hold one’s life, as if in a basket, while emphasizing the fact that baskets are typically woven; therefore, “they can be pierced.” Life “oozes” out of the cracks of a home, revealing a symbolic lack of structural integrity, so to speak.

The structures of the café and the hotel room in the city represent certain ideas of home that Adnan renders both appealing and dangerous. The writing itself is also an act of place-making: it’s the medium through which representations of home and belonging are rendered, and it’s a space of belonging in and of itself.

Theodor Adorno famously wrote that the exile sets up a house in his text; that, in writing, the one who no longer has a homeland can finally feel at home.

Expanding on this idea, Said writes:

“Adorno’s reflections are informed by the belief that the only home truly available now, though fragile and vulnerable, is in writing.” (“Reflections”)

Similarly, Adnan writes:

“I remember having written somewhere that my books (of poetry and prose) were, are, the houses that I inhabit. It’s true. And it looks simple. And it is not. Even here the harbor is not safe from trouble.” (VWE)

Form and content come together here in writing to construct yet another kind of home: beyond the space of the city, beyond nationalistic discourses; in the text, on the page.

However, Adnan also writes that “[e]ven here the harbor is not safe from trouble.” No where, then, is stable — not even the page. There are limits to language — both artistically and politically. As Said writes, writing is “fragile and vulnerable.” After all, meaning isn’t stable, so of course the text isn’t either. Language is political, and Adnan knows this from her years of French schooling in Beirut.

Moreover, during the Lebanese Civil War, Adnan realizes she’s automatically sided with the colonizer simply by writing (and speaking) exclusively in French and not Arabic. Coming up against the limits of language in such a poignant and political way, Adnan turns to a different mode of expression: that of visual art.

Although Adnan never composed literature in Arabic, she did practice writing Arabic when she was young. Her father tried (and failed) to teach her Arabic by basically leaving Adnan to her own devices: he gives her an Arabic-language book, a pen, and paper, and he tells her to simply copy everything from the book, to just write it all down and transcribe it directly onto the blank page. Adnan describes this experience, in Voyage, War, Exile, as actually quite fun for her because she enjoyed the physical act of copying Arabic script, of writing in a language she didn’t understand. This frees her from meaning-making in a way, and she cites this as a core memory leading her to eventually turn from writing to painting: remembering what it felt like to be free of meaning-making, to just move the pen across the page.

Combining the act of writing with the creative expression of painting, Adnan produces these beautiful leporellos that, for the sake of time, I won’t properly analyze here, but basically a leporello is a sort of accordion-style, folded piece of paper that unfolds horizontally across space to reveal an image or something painted on the paper. Adnan here essentially transcribes lines of Arabic poetry onto the leporello pages (along with other embellishments and images around the script) — resembling her early experiences of writing in Arabic. It’s important to understand Adnan’s multi-disciplinary art practice in this context. Writing presents limits for her in a way that painting does not, in the sense that painting can access a wider audience and doesn’t automatically implicate her in French colonial nation-state logics and discourses but instead sort of free her from meaning-making, thus also revealing the limits of the idea of writing as place-making.

"The metaphor of the house as a basket evokes the image of the house as porous, which stands in contrast to common conceptions of home as stable and contained. So Adnan is sort of letting us know that she’s well aware of the dangers of home: the way it purports to hold a life safely but inevitably fails to do so."

I wonder if "houses" in this instance are allegorical for Beirut, or the nation-state in general. Countries are the "houses" of nationalism that are conceived of as stabilizing forces. But she has experienced the fallacy of that with the destruction of "her Beirut." I haven't read Adnan, but I think there might be a relationship here worth considering if you haven't already.

Lovely piece!!