February Reads

Aria Aber, Naomi Shihab Nye, Jamaica Kincaid, and more

Welcome to the first installment of what will be a monthly recap of all the books I manage to check off my never-ending TBR list. Starting with February.

I spent a fair amount of time this month reading for the class I’m working as a TA in, but it’s always a treat to be able to do that because it reminds me that I’m literally getting paid to read novels, which is no thing to complain over. I do feel I may have cheated a bit with one of the reads this month because it’s not only a kind of gallery guide with many paintings and photographs of art by Afghan French performance and visual artist Kubra Khademi who I’m obsessed with right now, but the essays in it are written in English and translated into two other languages (French and German), which makes it seem like there’s more book to read, but there isn’t really. And anyway, I am a reading purist. I can’t even get into audio books because it just feels wrong. Other reads this month include: Aria Aber, Jamaica Kincaid, Naomi Shihab Nye, and more.

No-No Boy, John Okada

After serving a prison sentence for refusing to demonstrate his loyalty to the US, Okada’s protagonist Ichiro still experiences multiple modes of imprisonment for being a “no-no boy” upon his return home. His sense of confinement lingers. Ichiro is labelled “no-no boy” because, like many Japanese Americans at the time, he refused to pledge his allegiance, over Japan, to the United States of America during World War II. As a no-no boy, Ichiro feels ashamed of his choice to abandon his American identity and the country he was born in, and at the same time, he knows he couldn’t bring himself to betray his mother and ancestors by siding with their enemy. The novel explores Ichiro’s confrontation with this paradox of citizenship as he navigates the psychic and existential pressures of being both American and Japanese — and a no-no boy. Does he relinquish his Japanese identity and embrace his American identity? Or does he craft a new kind of Japanese American identity?

I had to read this for the class I’m TAing for this quarter on comparative ethnic literature in the US. I found Okada’s prose a bit hard to get into — it’s neither realist nor modern, so it can feel a bit choppy as it winds through scenes of stark realism and dream-like sequences — but I’m glad I got the chance to sit with it.

Words Under the Words, Naomi Shihab Nye

I had the opportunity to spend a bit of time with Naomi Shihab Nye during her campus visit in February. She led a poetry workshop for students one evening and sat down with some faculty and graduate students for a luncheon the following day. I don’t know what I was expecting Naomi Shihab Nye to be like in person, but I don’t think I was expecting what I discovered that first evening when I attended her poetry workshop. She has the effortlessly cool energy of — stay with me here — a rock singer. I don’t know how else to describe it. Think Patti Smith or Stevie Nicks or something. She has a powerful, deep, raspy voice, and her signature side-parted side ponytail rested on one side of her neck in light tones of brown and silver. And when I say ‘cool,’ I don’t mean indifferent or disengaged. In fact, Naomi was the opposite. She’s one of those masters who not only cares about everyone’s story and what they have to say, but she truly believes that everyone has a poem inside of them. There was something so peaceful and serene yet powerful about her presence — it’s still hard for me to put into words even as I write this a month later. I wrote a short dispatch about the poetry workshop, which you can read here if you’re interested.

The poems in Nye's Words Under the Words are intimate, comforting, and evergreen. These poems — both epic and simple — are stories: about family members, friends, and strangers who touch the poet tenderly and fiercely whether they know it or not.

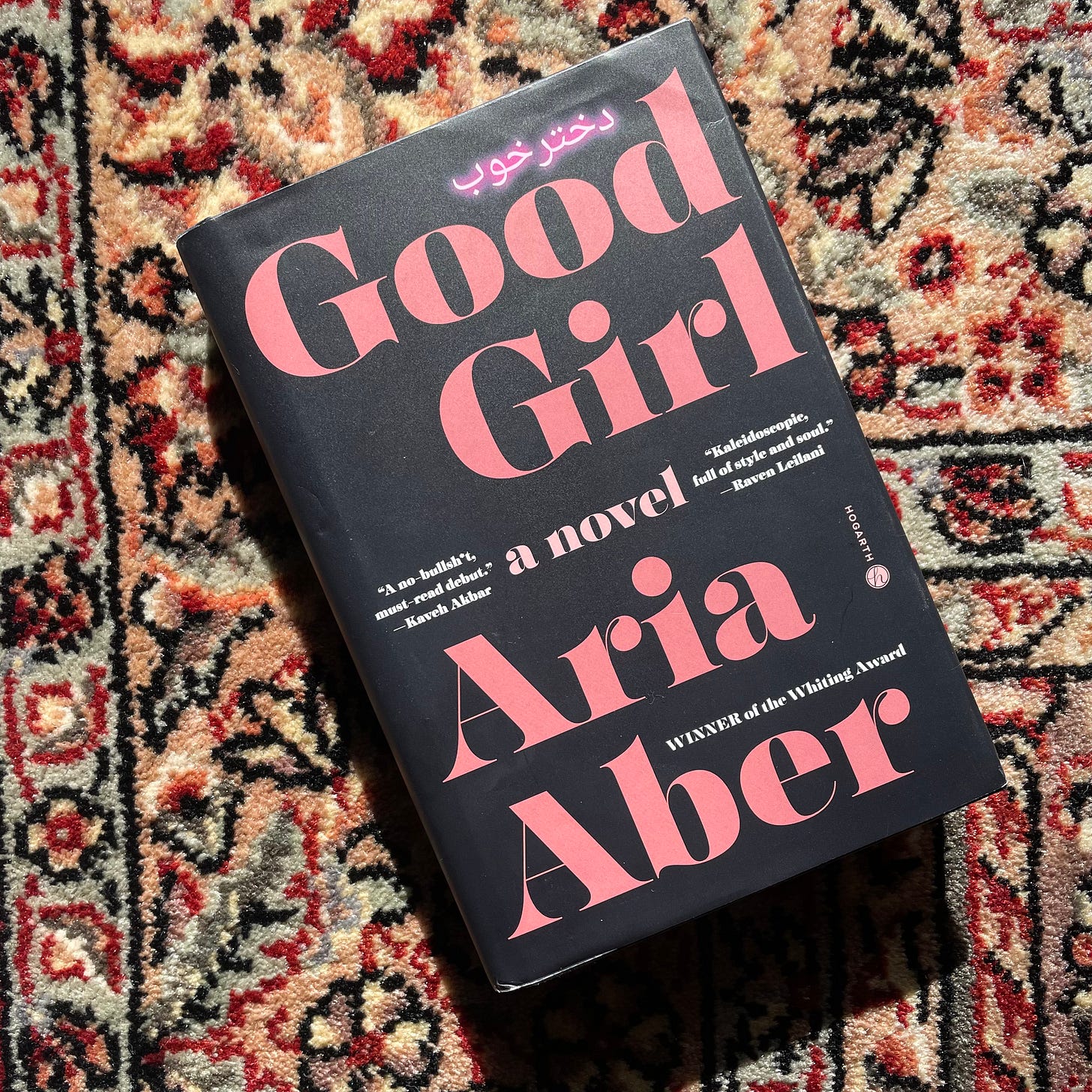

Good Girl, Aria Aber

If you’re in the same literary corner of the internet as me, then you’ve probably seen some hot, chic press release about Aria’s debut novel at some point in the past weeks or months. I’ve been waiting for this ever since I first read Aber’s Hard Damage, and it was such a treat to finally get so many delicious pages of Aria’s prose. I found her protagonist Nila absurdly frustrating at times, but Aber treats her with such tenderness throughout the text that I can’t help but feel for her — and even identify with her. Nila is just a girl. And she wants to get free. There’s so much depth and range here: it’s fun, funny, hot, disgusting, smart, tragic, existential. And a real masterclass in making the move from poetry to fiction without losing that sort of mystical shape and texture of one’s poetic voice and sensibility.

I finished this book by reading it first thing in the morning, from bed, as soon as I woke up, which is not my typical reading practice, but it was an almost euphoric experience to read in bed bathed in sunlight and soft, warm sheets; my body bare and still holding onto my love’s heat. (Note to self: do this more.)

Kubra Khademi: Political Bodies, Hanna G. Diedrichs Genannt Thormann (ed.)

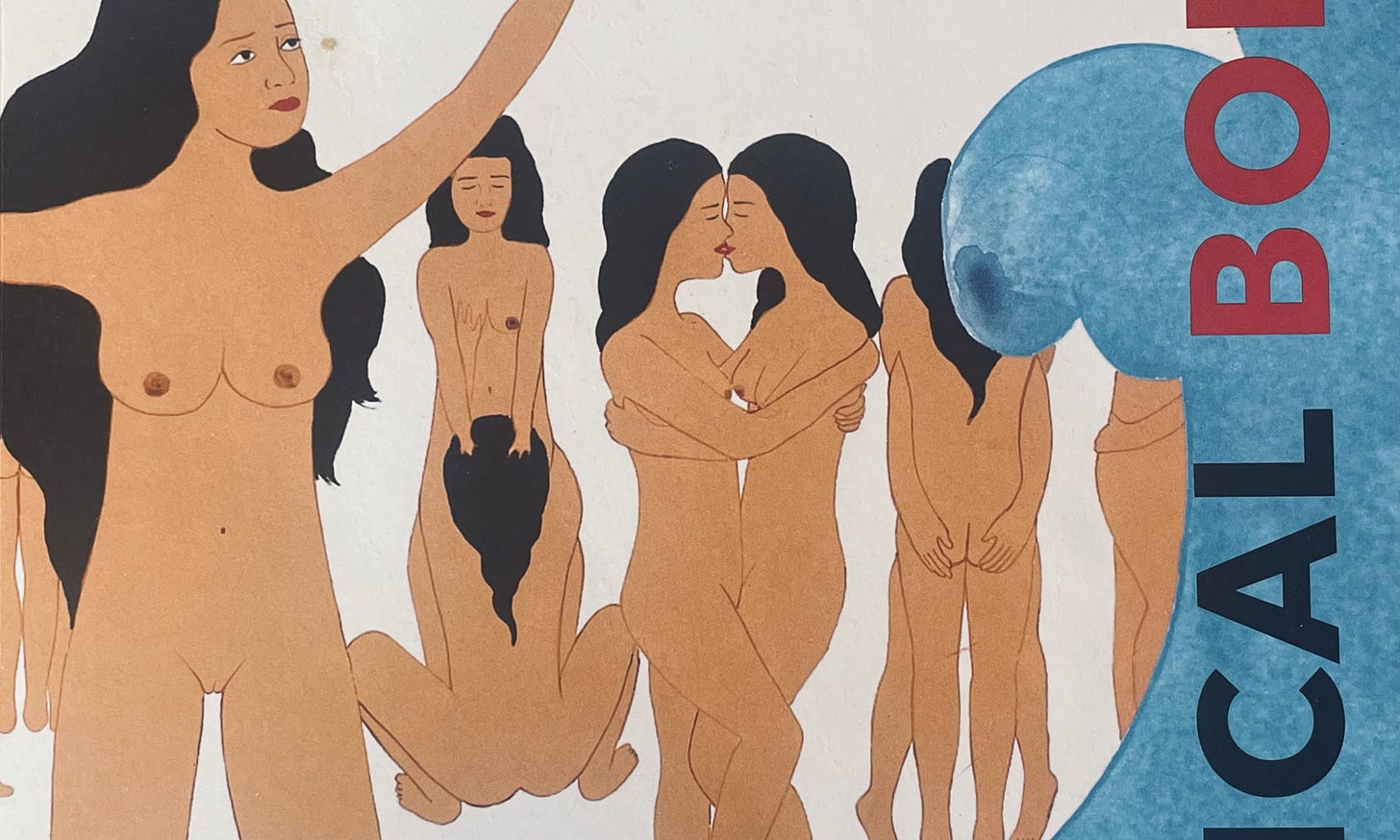

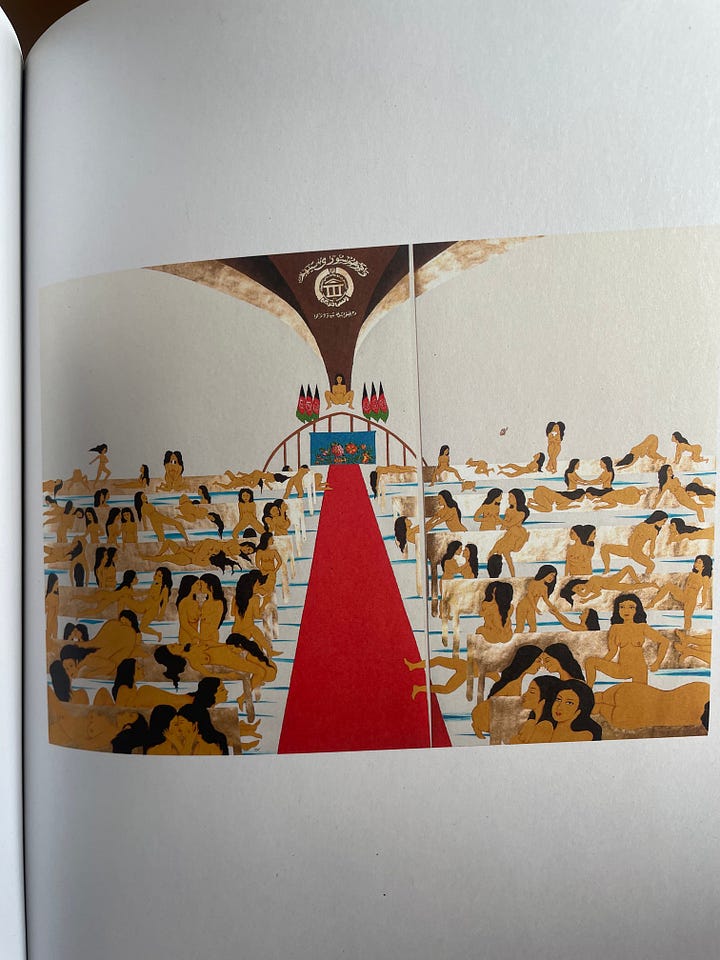

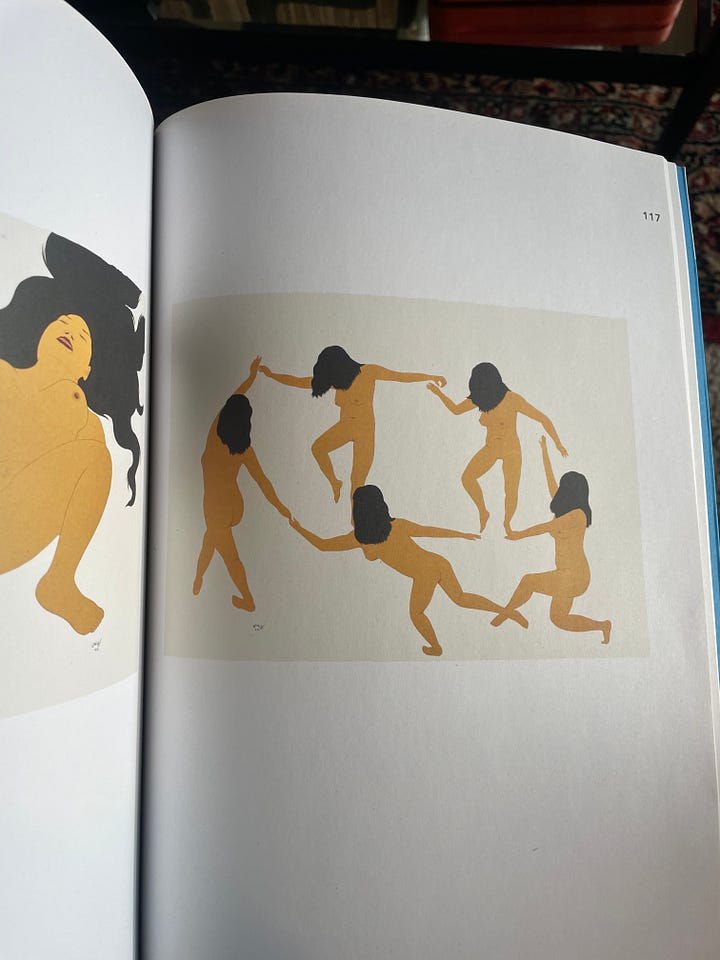

I only recently discovered Afghan visual and performance artist Kubra Khademi, and holy shit I’m so glad I did. Her work is radical and powerful and tough, and at the same time, there’s something really tender, soft, and romantic in her representations. A recurring figure in Khademi’s visual art is the naked woman’s body taking up various configurations in space. She paints the same body — modeled after her own — so that, when there are many women depicted in a painting, they sort of look like clones. In one painting, Untitled (Cinq femmes en dansant) (2019), the women hold hands and form a circle, à la Matisse’s dancer’s, but Khademi’s figures look more like they’re stumbling than dancing. In another, Parliament Scene (2021), a crowd of women are depicted in a kind of minimalistic, somewhat abstract rendering of a parliament meeting room. Afghan flags are raised at the front of the room surrounding a woman sitting at the head of parliament with her legs spread open. The women in the seats of the parliament room are mostly coupled together, making love. I simply love these paintings. I’m so captivated and moved by them — I feel like I can’t look away. The role-reversal of women taking up space in Afghanistan’s political sphere is already a radical representation; and on top of that, the women are naked and and engaging in sexual acts. I think the sex is necessary here not exactly as a statement or representation of free, queer love (although, in some ways, it encompasses that ethos) but rather as a reclamation of women’s sexuality in particular — no matter what form it takes — and a renunciation of the sexist, misogynistic, male-dominated mode of governance in Afghanistan that works tirelessly to control women’s bodies and sexuality.

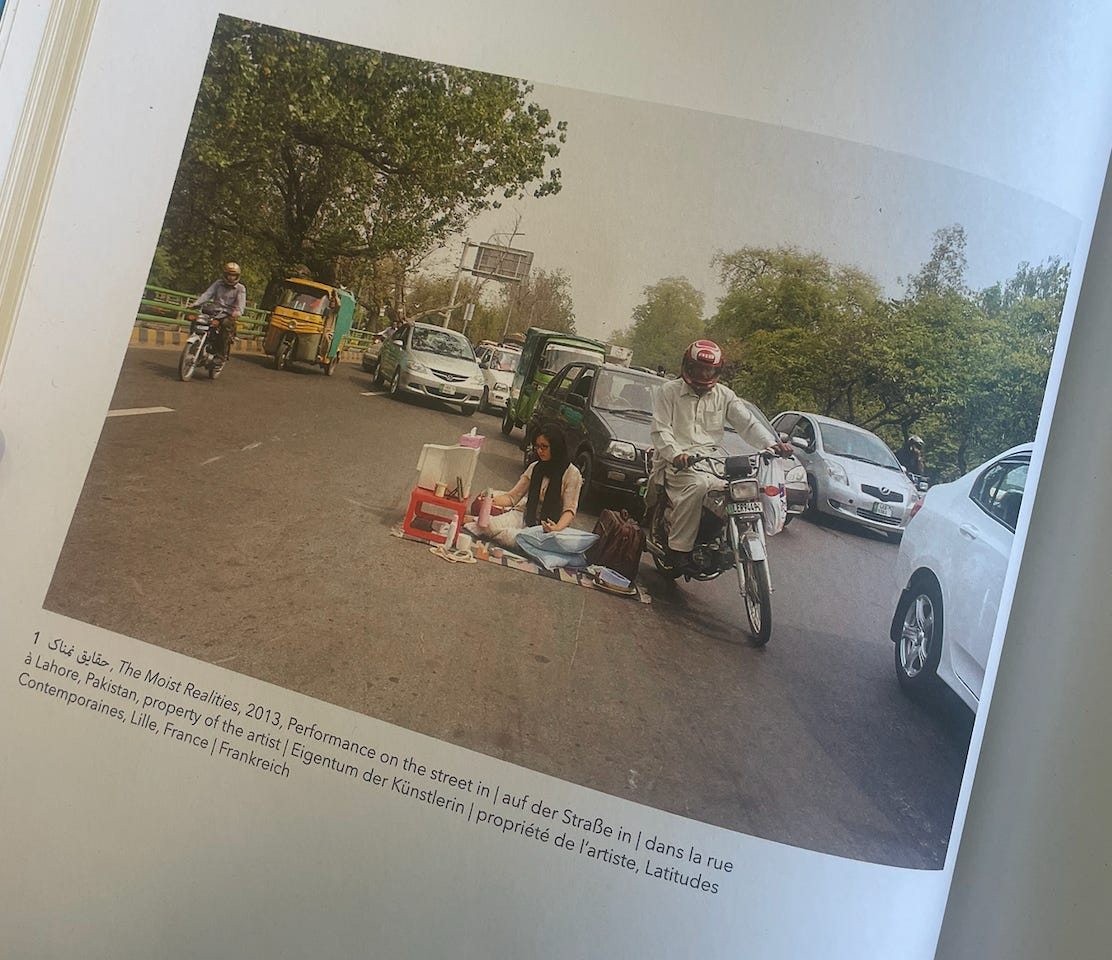

Just as she reclaims space for women abstractly in her visual art, Khademi reclaims space literally in her performance art. Illustrating the relation between the state and the street, Khademi uses her body to physically take up space in the public sphere, disrupting, momentarily, society’s sense of order. In one particular performance piece, The Moist Realities (2013), Khademi sits on a small blanket in the middle of a thoroughfare and performs mundane tasks, like smoking and reading. The book features a photograph of the performance, taken precisely at the moment a man on his motorbike suddenly veers around Khademi’s blanket, just barely missing her. There are other bikes and cars coming up behind him and behind Khademi, but she remains still there and lets the traffic wash over her. By holding up traffic through her performance, she reverses the role of men disrupting women on the street, as women in Afghanistan (and other places in the Middle East) face the constant threat of sexual harassment and assault when out in public.

I’m just obsessed with Khademi’s art, and I can’t wait to find her a home in one of my dissertation chapters. This book was an incredible introduction to her work, and I’m so glad that it exists and that Khademi and her art exists and that women exist.

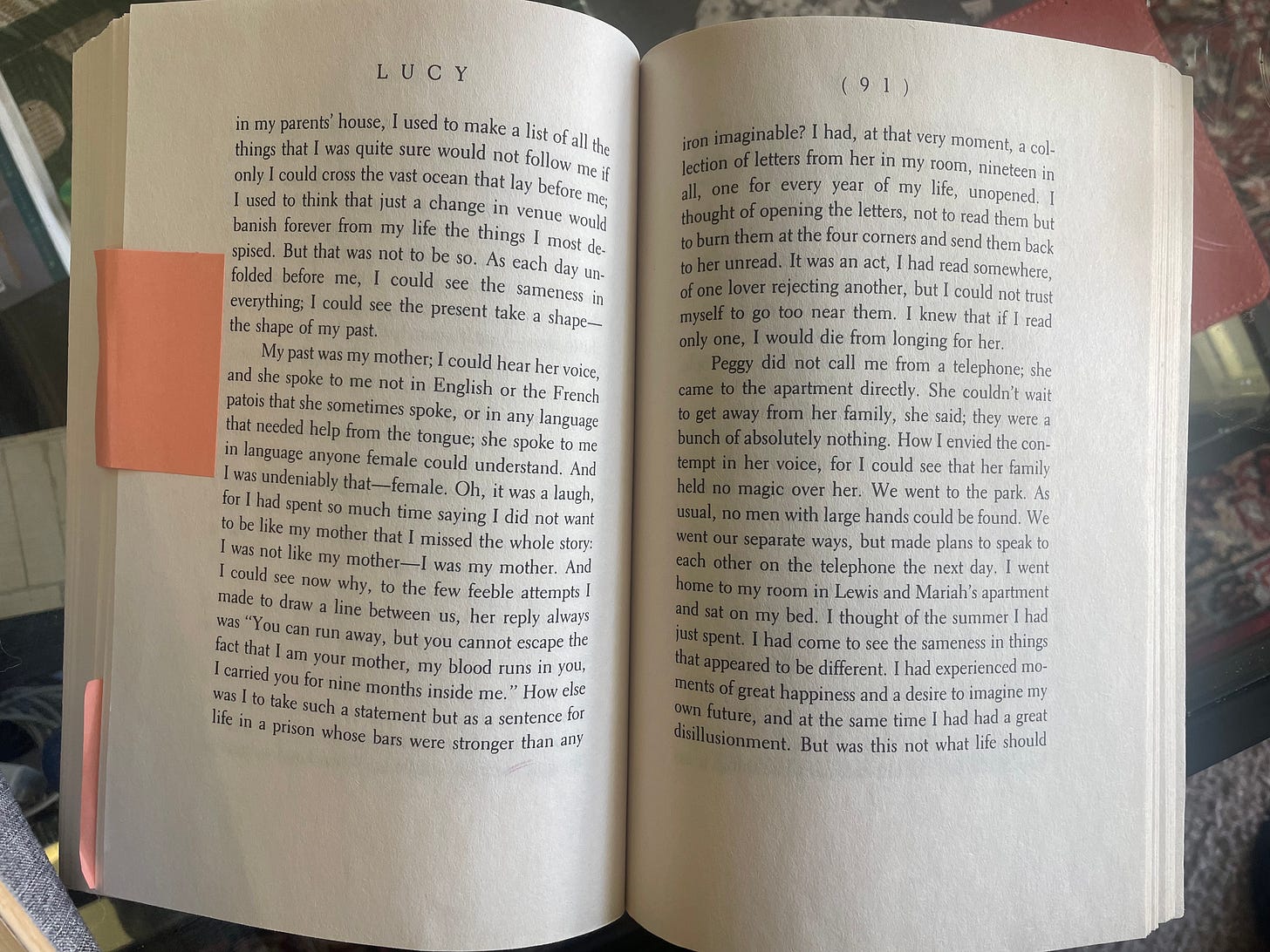

Lucy, Jamaica Kincaid

This was another one I had to read for the class I’m TAing for, and I’m still thinking about my professor’s beautiful lecture on it, which was weeks ago at this point. The main question my professor posed to the class in her lecture was: Is Lucy’s rebellion successful or not? Lucy’s mainly rebelling against her mother, but her mother represents for Lucy an entire way of living and being that she’s left behind — one that, crucially, she’s chosen to leave behind. I loved diving into this question with my students in section, and I loved reading this book. It’s so beautiful. It’s a story about a young woman choosing to leave her home and all that she’s known, in search of a different way of living. But it’s also about a young woman questioning what it means to be a woman, in search of a different way of being.

I wrote an essay on Lucy alongside my students writing their final papers because I just couldn’t get this book out of my head. You can read the essay here.

Who Sings the Nation-State?, Judith Butler and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

My copy of this book, which I found at the library, is small and musty and a bit tattered. It has a bright red cover with no words on the front, and the texture on the surface feels almost like linen but tougher. Inside is the transcript of a conversation between Judith Butler and Gayatri Spivak (but really it’s more like Butler going on about Hannah Arendt for about 75% of the book) where they theorize and discuss the idea of the nation-state and its material impact on notions and expressions of citizenship and belonging. I really appreciated Butler’s sustained reading of Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism, which helped me better understand Arendt’s conceptions of nationalism and belonging. I initially picked this one up because 1) it’s short and 2) it’s a transcript of a conversation — both things I thought would contribute to a slightly more casual reading experience. I was mistaken. It’s relatively brief, yes, and it’s technically just a conversation between colleagues, but it’s cerebral as hell. A necessary read for the diss, but one I’m glad to have gotten out of the way.