Welcome back to my monthly book report where I recap the books I manage to check off my never-ending TBR list. Here’s March ~

I thought I’d be able to get through more books in March, but that simply wasn’t the case. I wish I could say I got a ton of writing done as a result, but that simply wasn’t the case either. I got through four books this past month, and at the very least I can say that I feel quite fulfilled in having added them to my personal canon. Quality over quantity, I guess.

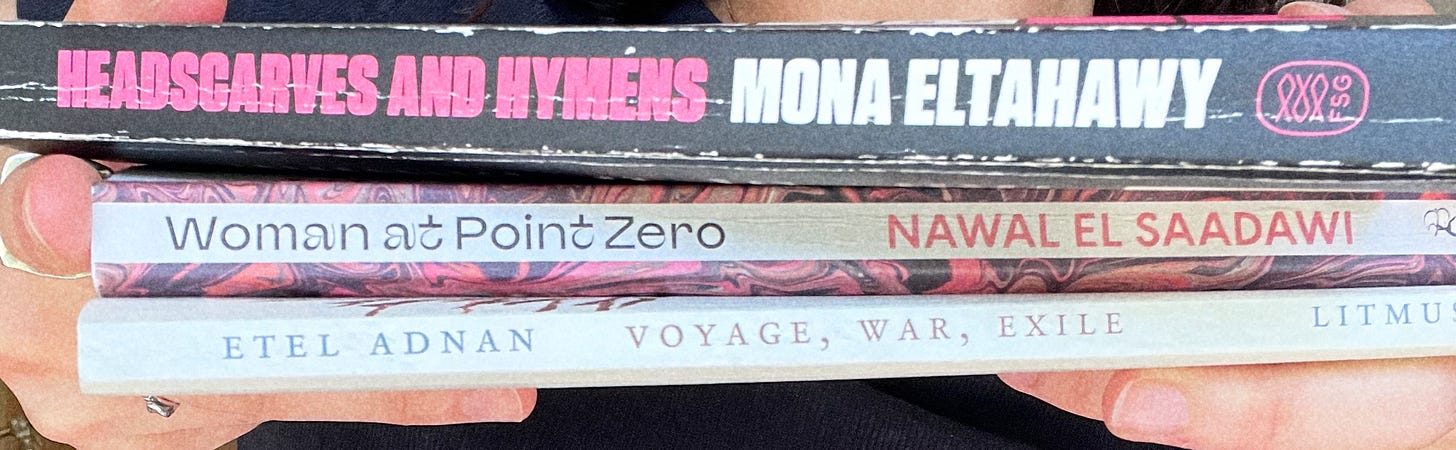

These texts quickly became very important to me (and, in some cases, to my dissertation). However, they weren’t all so easy to read. Eltahawy and El Saadawi write about some pretty heavy topics, which, in all honesty, were quite difficult for me to get through at times, which may have something to do with why I only had the bandwidth for a smaller set this month.

Maybe it is a quality over quantity thing. Besides, Goodreads tells me I’m not only on track to meet my modest 2025 reading goal, but I’m actually four books ahead. So let’s just say I was catching my breath in March.

Ex-Cities, Hélène Cixous (trans. Laurent Milesi, ed. Aaron Levy)

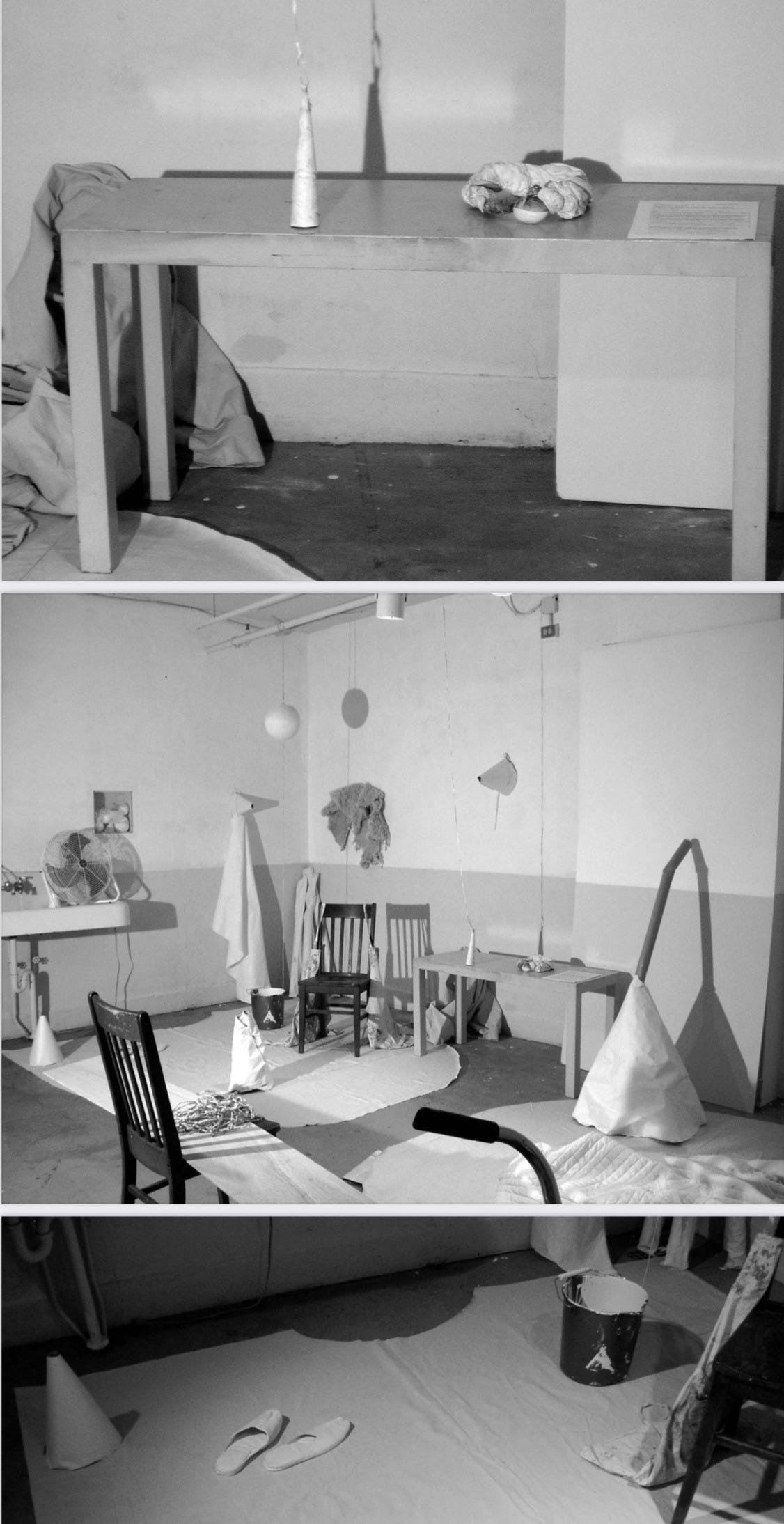

This book is constructed around a lecture Cixous gave in the early-2000s titled “Promised Cities,” which “takes displacement and exile as its points of departure in exploring the relation of art and literature to cities and their destruction,” as Aaron Levy writes in his introduction. It also features photos from an exhibition by British artist Maria Chevska, titled “Vera’s Room,” whose work also engages with exile and displacement but from the perspective of domestic spaces (as opposed to the figure of ‘the city’ in Cixous’s work).

The central figure of Cixous’s lecture is what she calls “the desired city” or place of origin. For Cixous, this is Oran in French Algeria. But Oran is lost to her; she’s removed from her place of origin, and all she can do now is yearn for it. The desired city is destroyed, taken by history, lost — sometimes literally, sometimes figuratively. Cixous meditates on the destruction of the desired city in the context of the age of urban catastrophe — in particular, Cixous reflects on the destruction of New Orleans, issuing a kind of call to action and emphasizing the necessity of responding to catastrophe both politically and artistically. She stresses the importance of reconstructing the lost city: “Not forget it. Not bury it. Recall it.”

The destruction of place, Cixous theorizes, creates the condition for possibility. She writes that the destruction of cities is “a bad thing which causes an art.” In this case, literature preserves the memory of what has been lost. Like a kind of archive, literature contains the memory of the lost city and thus remakes it. Places, however, are also archives, Cixous writes: “Places archive us and act upon us.” Places contain our traces, the various traces of our existence. Places contain us, our lives, and our memories. Places happen to us.

I’m still trying to wrap my mind around this rather esoteric book. It’s hard for me to engage with it without getting esoteric myself.

I’ll leave you with some quotations:

“Though I never saw my cities with-my-eyes-of-flesh, I would at least have ‘seen’ them with my ears, I inhabited their names, their sounds, I tasted them through all my senses, traveled them spelling them out, . . . I sucked their juice, their bones, I did not inhabit the name Paris, it never came to my mind, I cried enormously in Oran . . .”

“To tell the truth I do not feel any nostalgia properly speaking. On the contrary. Using the word nostalgia bothers me, betrays me. What I meant was ‘yearning.’ To come back to my cities and their languages.”

“The destruction of the city. Is it a good thing is it a bag thing? It is a bad thing which causes an art. A sorrow that causes. Literature is a field of destruction a field of ruins, the song of ruins, the archive song of ruins.”

Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs A Sexual Revolution, Mona Eltahawy

This book is such an important read. Its contents may be hard to swallow, but Eltahawy’s voice is so powerful, moving, and even welcoming.

In Headscarves and Hymens, Eltahawy reports — with style, strength, and integrity — on the condition of women in certain parts of the Middle East and North Africa. She insightfully highlights the relationship between the state, the home, and the street, emphasizing the interconnectedness of the patriarchal powers violently governing women’s bodily and sexual autonomy in these three intertwined sites. This triangulation is an important reminder of how revolutions on the street must also be taken into the home before they infiltrate the state.

Women in certain countries in the Middle East and North Africa are not only unsafe under the law, with no meaningful protection from or recourse to sexual assault, but they’re also unsafe on the street, facing the constant threat of harassment and assault in public spaces. The condition of women in public spaces is essentially one of exile. But the home isn’t exactly safe either, with many sexual assaults beginning in the private space of the family.

Eltahawy writes a controversial book, and she suffers the consequences of that. It takes a lot of courage to have intellectual integrity and consistency. Her critique of Islam is so fierce that it’s no surprise people have (as she recounts in the book) linked her critiques of the religion, and its enmeshments with culture, to xenophobic right-wing talking points. Of course, Eltahawy’s politics are not actually aligned with the right-wing pundits who spew talking points about Islam as “degraded” or Arabs as “backwards,” but she does lift the veil (no pun intended) on the gross entanglement between culture and religion in the region, in the name of women’s liberation and bodily autonomy. Meanwhile, leftsts, as Eltahawy explains in the book, tend to be too concerned with “cultural sensitivity” toward communities practicing Islam, such that they suspend critiques of the patriarchal conflation of culture and religion in those very communities, which women suffer the consequences of the most.

Eltahawy beautifully weaves the personal with the political here, sharing her own experiences as someone who previously practiced Islam and ultimately untangled her sense of self and womanhood from its dictates. Eltahawy’s vulnerability in sharing her journey with the hijab, from putting it on to taking it off, is courageous. She writes about how she shares this story with her students sometimes too: sharing something personal with them so that they may soften up or feel empowered to perhaps do the same.

Eltahawy also cites a particular strand of transnational women of color feminism as helping her and the women she works with to gain a kind of consciousness of their condition in particularly extreme contexts of violence against women, female genital mutilation, and overall patriarchal control informed by a disgusting misogyny that claims women’s bodies for their own.

Reading this reminded me also of exactly the kind of feminism that I still believe in. The women Eltahawy writes about (including herself) need feminism. It’s material and life-affirming.

Woman at Point Zero, Nawal El Saadawi

Eltahawy references El Saadawi and Woman at Point Zero in Headscarves and Hymens, and it’s been on my TBR for a while now, so I thought this would be the perfect follow-up to Eltahawy. I wasn’t wrong, but it was definitely difficult to follow one heavy book with another heavy and dark book.

It’s hard to call this a novel because it’s made clear from the beginning of the text that this is based on a real experience El Saadawi had. Woman at Point Zero is written in a style that reminded me of (stay with me here) Conrad’s Heart of Darkness or Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. It’s written as a recollection. The narrator is fashioned as a version of El Saadawi herself, as this is based on a true story, a true thing she experienced. The narrator visits a woman in prison, in solitary confinement. The woman’s name is Firdaus, and she’s in prison because she murdered a man. (This isn’t a spoiler.) Firdaus agrees to meet and talk with the narrator. Firdaus (re)tells the narrator her story — how she ended up there, in solitary confinement, awaiting her execution — and the narrator transmits her story to us, the readers. It’s the story of Firdaus’s life that she finally gets to tell herself.

We learn that Firdaus went through female genital mutilation as a child; and that she’s repeatedly assaulted by different men in her family, namely her father and uncle. Eventually she gets married, and her husband rapes her too. He also beats her, and one day, when it gets really bad, Firdaus manages to run away. The streets, despite the danger they present, take her in, and there she begins her a nomadic life of falling into frankly really shitty situations with men who offer her basic comforts: not sex or love or companionship but literal shelter, fresh clothes, a shower. Eventually, Firdaus meets an older woman who teaches her that she can at least make these men pay her if they’re going to force themselves on her, which is exactly what Firdaus goes on to do.

Throughout her story, Firdaus repeatedly describes her experience of pleasure and desire as being far away, removed, distant, detached. She repeatedly refers to experiencing pleasure as a distant memory, like something she’s been cut off from, something that’s simultaneously behind a thick fog and at the same time very painful, like a fresh wound. She never quite names it, but we can infer that this has something to do with her having been cut when she was a girl: exiled from her own body, the very source and center of her own pleasure and therefore power.

The men Firdaus encounters throughout the story wound her both physically and psychically. One day, in an almost flash-like moment of self-defense, she murders a man who was harming her — not because he was causing her more pain than the others, or because he was markedly worse than the rest of them, but because, in that moment, he comes to stand in for every man who’s ever wronged Firdaus, from her father to her husband. Firdaus, overcome with emotion in the heat of the moment, takes a knife and stabs the man. She remembers how easy it was to insert the knife into his flesh. How, if she’d known how easy it was, she might have done it sooner.

By the end of the book, Firdaus is taken away to her death, and El Saadawi walks away with the overwhelming feeling that she may have just met the most courageous person on earth.

This book devastated me. There’s no other way to say it. It’s tragically beautifully painfully raw.

Voyage, War, Exile, Etel Adnan

It’s safe to say I’m a huge fan of Etel Adnan, and I can tell you right now this won’t be the last book of hers I read this year. I’ve been working my way through her oeuvre for about a year now, and she’s quickly become one of my favorites of all time.

Voyage, War, Exile is a collection of three essays translated for the first time in English and published just this year. I found this collection very useful in better understanding the context in which Adnan was writing, and I liked that they were written as personal essays. It felt like a very intimate collection, almost like a mini-autobiography. I’d recommend it to anyone interested in Adnan but intimidated by her work (she can be cerebral and dense at times). This is really a portrait of the artist as told by the artist. This book also proved to be quite important to my dissertation, and it eventually made its way into a conference presentation, which I posted to my newsletter last week.

I’ll keep it brief on this one and leave you with some quotations:

“Riding in a car on the American highways was like writing poetry with one’s whole body.”

“A poet is, above all, human nature at its purest. That’s why a poet is as human as a cat is a cat or a cherry tree is a cherry tree. Everything else comes ‘after.’”

“Writing (or art) seem to be the only meaningful activity when one is uprooted: it gives form and substance to what other wise would be a devouring chaos.”

Thank you for the recommendations.