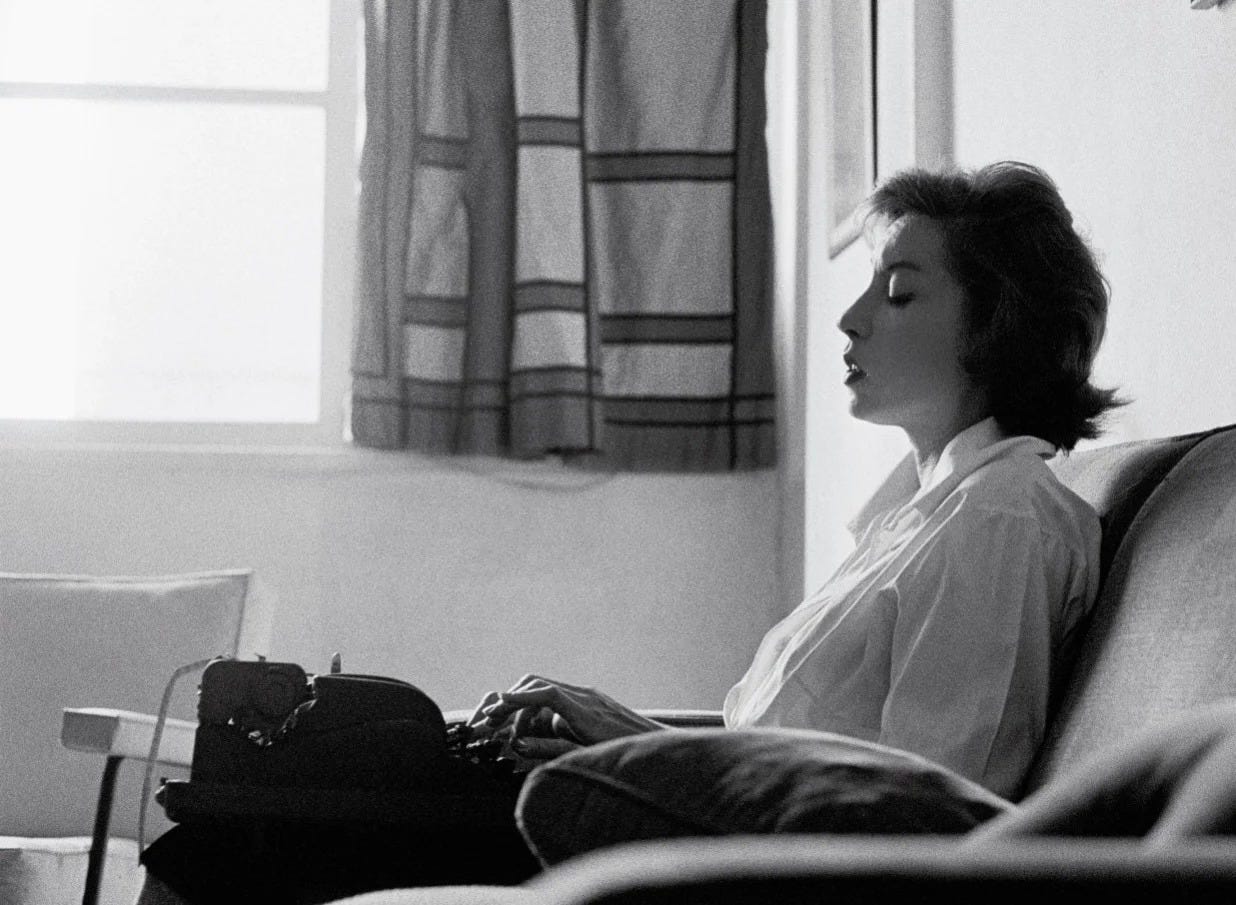

Magical wielder of language Clarice Lispector once claimed that she would write without words if it were possible.1 And I think I agree with her. Sometimes the burden of meaning making through the written word is simply too heavy. Sometimes it’s too difficult to carry sense in a sentence. This is why I love poetry. Poetry doesn’t require one to necessarily make sense. That’s not, nor has it ever been, the main goal of poetry. Poetry exists in relation to song, sound, music. It’s not concerned with semantics, meaning, reason. This is also why I love writing poetry. It frees me from feeling like I must make myself make sense on the page.

Feeling liberated from this constraint is also vital to my well-being as a graduate student. Faced with the seemingly insurmountable task of writing a dissertation, I’ve never been more aware of how writing in different modes feels like working out different muscles. Writing a dissertation requires a certain kind of rigidity (one that I’m afraid I’ve yet to accept in my own process), which, frankly, I find quite boring. Although it’s possible to write a poem that demands a research process, a dissertation nevertheless presents the findings of that research in a very different way. Although it’s possible to stage political and social critique in poetry, dissertations present those critiques differently. My point here isn’t to detail the differences between dissertations and poems. What I really mean to say is: you can say the same thing in very different ways. Perhaps this is obvious, but I suspect we take it for granted more than we realize.

However, one thing poems and dissertations have in common is the fact that both forms of writing can be (and often are) rather esoteric — and this is allegedly what gives them both value. In an episode of the LARB Radio Hour, a podcast from the Los Angeles Review of Books, writer and critic (and former academic) Andrea Long Chu talks about how academia “is not supposed to be for everyone.” This comment comes in the context of a discussion about journalism’s relationship to the reader versus academia’s relationship to the reader. Chu states that “academia is about knowledge production,” while being a critic “is about some kind of relationship to the reader.” There is a certain readership for academic writing, to be sure, but it’s not a “reading public,” as Chu explains. And, she goes on, that’s precisely the point. There isn’t supposed to be a reading public in academia. “If it is to have value, it kind of needs to be cloistered and esoteric,” Chu says. I do think academic writing can be esoteric. In my field (literary studies), not only is the writing sometimes esoteric, but the primary texts themselves are often esoteric. Moreover, I can admit that my taste in literature has grown increasingly esoteric since starting graduate school.

Many people also think of poetry as categorically esoteric, which is why most people don’t read poetry. “No one listens to poetry,” as San Francisco Renaissance poet Jack Spicer writes in “Thing Language.” The excuses I’ve heard over the years ring in my head as I write this: “But I don’t know how to read poetry,” “I just don’t get it,” “It reads like a lot of jumbled words.”

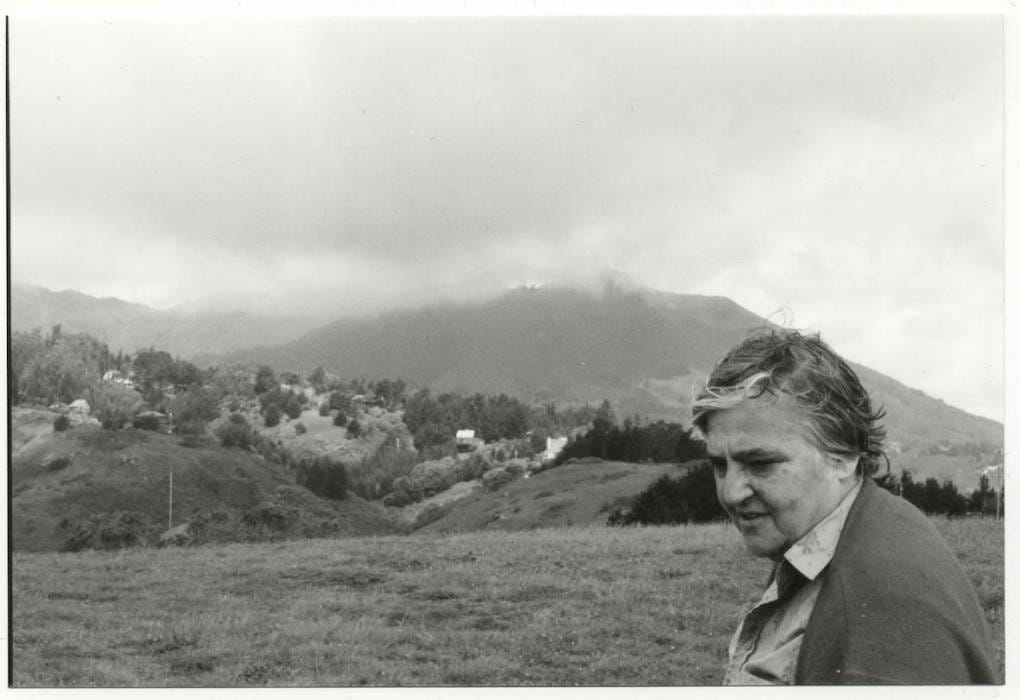

In an interview published in The Sun on the Tongue, Lebanese American writer and poet Etel Adnan helps illuminate what exactly makes a piece of writing poetic. She explains, “Two people can read the same line, one will say: it’s poetry, and the other: no, it’s just information. Sure, it’s information in both cases, but there are different responses.”2 In other words, you can have a “poetic” response to the very same thing that triggers a “rational” response in someone else. Poetry is perception. Poetry is a paradigm: a way of reading and seeing the world — one which you can choose. Adnan says, “Any subject matter can be poetry, if you decide it is.”3 We choose poetry; anyone can decide anything is poetic at any moment. That’s poetry. Poetry can imbue something as banal as a grocery list with a great aura of mystery. Or, as in Adnan’s example, a piece of bread: “The piece of bread becomes mysterious. Because it is mysterious. Everything is mysterious. But we don’t take the time to see that.”4 If you take the time to look twice at the supposedly ordinary thing, you might start to realize it’s actually a miracle.

Poetry is the movement from the banal to the metaphysical. French filmmaker Agnès Varda once said, “Nothing is banal if you film people with empathy and love.”5 Poetry is like this: a lens, like that of a camera, through which one can look at the world with empathy, love, mystery, curiosity.

However, there might still be a relationship between poetic writing and philosophical writing. For instance, Adnan sees German philosopher Nietzsche as a poet. “When you read Ecce Homo,” Adnan says, “you realize that it’s a lyrical piece. . . The boundary between poetry and philosophy has been erased to a great degree. Why? Because of the subject matter.”6 Adnan explains that poetry used to take nature as a common central theme or topic, but in the twenty-first century, poetry increasingly expresses ideas. There are still nature poems (and thank god for that), but there are also idea poems, theory poems, poems that engage with the conceptual more than the material or natural world. As Adnan says about Nietzsche, this shift blurs the border between theory and poetry. I know a professor who always advises her students to read theory like poetry and poetry like theory — and honestly I think it works.

In a letter from Virginia Woolf to Vita Sackville-West (Woolf’s friend and former lover), Woolf writes, “Is it true you grind your teeth at night? . . . What and when was your moment of greatest disillusionment?”7 These two questions are written consecutively, uninterrupted by other words or phrases; the ellipsis are transcribed here exactly as they appear in the original. In the same breath, then, Woolf goes from asking Sackville-West about something mundane (grinding teeth) to asking her about something quite profound (moment of greatest disillusionment). This is another example of movement from the banal to the metaphysical. The pairing of these questions suggests a relationship between banality and a sort of wonder. Interiority is illuminated in this move from banal — but intimate: as if Woolf longs for a silent night next to Vita, to be so still and quiet beside her that she could hear teeth grinding — to grand. To learn of one’s moment of greatest disillusionment is to learn of a transformative, pivotal, and significant moment in that person’s life, which facilitates intimacy and an unfolding of interiority. Within each person is a vibrant inner life. The question is how to illuminate that vibrancy in its entirety.

Poetry works like this, too. It moves from banal to metaphysical — but only when we choose to stop and look at the words on the page. Only when we take the time to look twice will the color in anything illuminate itself. And Adnan reminds us that it’s “no coincidence that, historically, the traditional ancient works combining words and images were called by the magic name of Illuminations.”8 This process of “illuminating,” or combining words and images, echoes Woolf’s combination of banality and profundity, which illuminates Vita’s interiority. If we choose to look at the world around us with this kind of wonder — the kind that Woolf has about whether Vita grinds her teeth at night or the kind Varda has when filming her subjects — we’ll start to see the poetry in everything. In yet another echo of Woolf’s meticulous attention to the sheer presence of another being, which is a way of looking with love, Adnan writes, “Love begins with the awareness of the curve of the back, the length of an eyebrow, the beginning of a smile.”9

Poetry works like this, too. It starts with the awareness of the curve of a vowel, the length of a line, the beginning of a couplet. It starts with awareness — and looking with love.

“If I could write by carving on wood or by stroking a child’s head or strolling in the countryside, I would never resort to using words.” Clarice Lispector, “The Making of a Novel,” from Selected Crônicas, trans. Giovanni Pontiero (New York: New Directions Books, 1992), 140.

Etel Adnan, “Thinking as a Form of Poetry,” in The Sun on the Tongue, ed. Bonnie Marranca and Klaudia Ruschkowski (New York: PAJ PUblications, 2018), 20.

Adnan, “Thinking as a Form of Poetry,” 21.

Ibid.

From Varda by Agnès (dir. Agnès Varda, France, 2019).

Adnan, “Thinking as a Form of Poetry,” 20.

Virginia Woolf to Vita Sackville-West, October 14, 1927, in The Letters of Via Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf, ed. Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell A. Leaska (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1985), 240.

Adnan, “The Unfolding of An Artist’s Book,” in The Sun on the Tongue, 61.

Adnan, “The Cost for Love We are Not Willing to Pay,” in The Sun on the Tongue, 67.

Subscribed!

“Only when we take the time to look twice will the color in anything illuminate itself.”

Is my favorite sentence now.