The speaker moves between proximity and distance, but the city nevertheless maintains its position as fundamentally displaced.

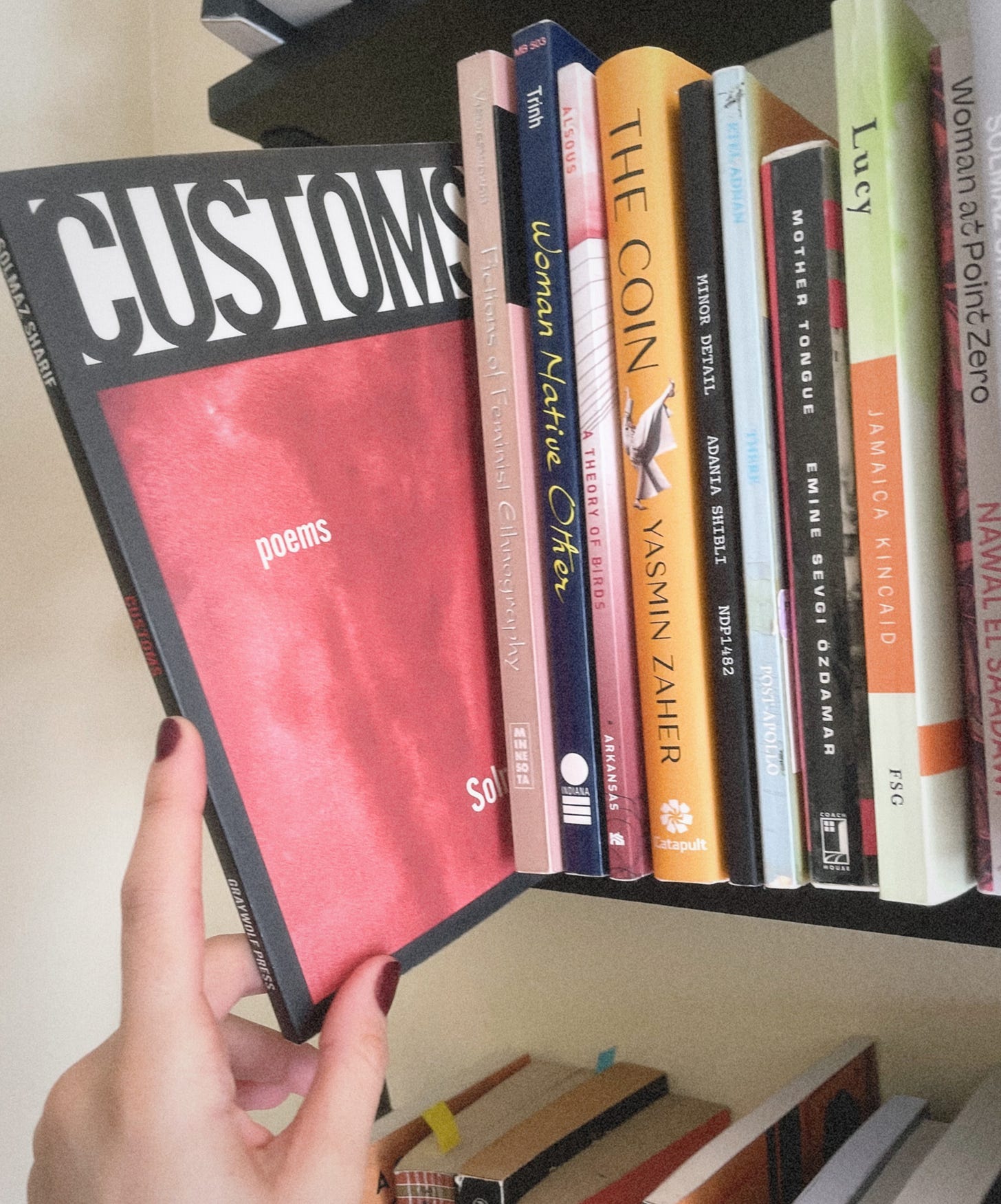

Two weeks ago, I spent the entire weekend analyzing Solmaz Sharif’s poem “The End of Exile” from her 2022 poetry collection Customs — and did little else.

I think of my close reading process as a kind of raw data collection. I work out an interpretation of the primary text before superimposing any kind of theoretical framework onto my reading. What you see below is this raw data: a first pass at close reading the poem without worrying too much about how my analysis might fit into the larger project with regard to different thinkers I’m in conversation with, like Homi Bhabha, Edward Said, Jacques Derrida, Hélène Cixous, and others (although Cixous makes a brief appearance here because I apparently can’t get her out of my head).

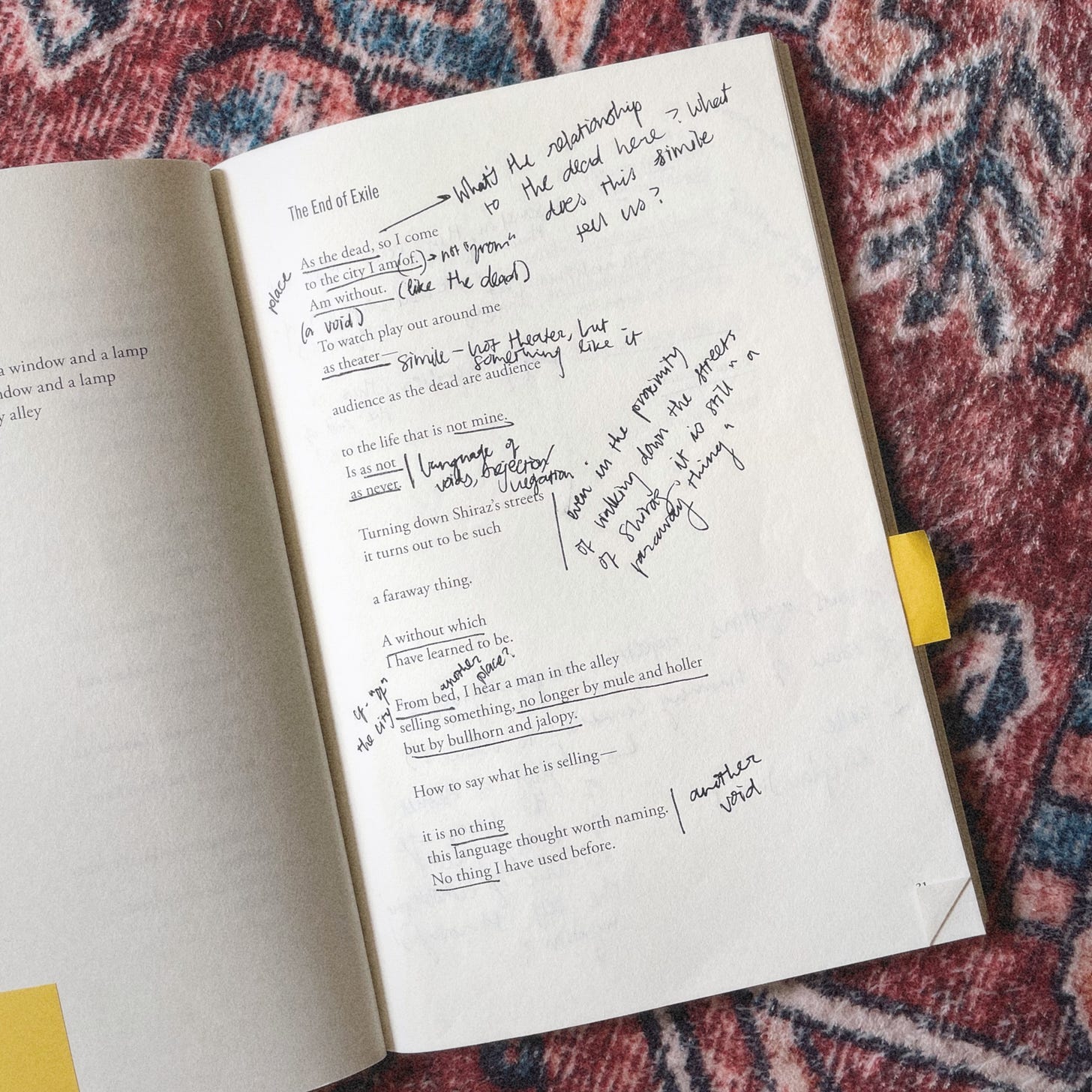

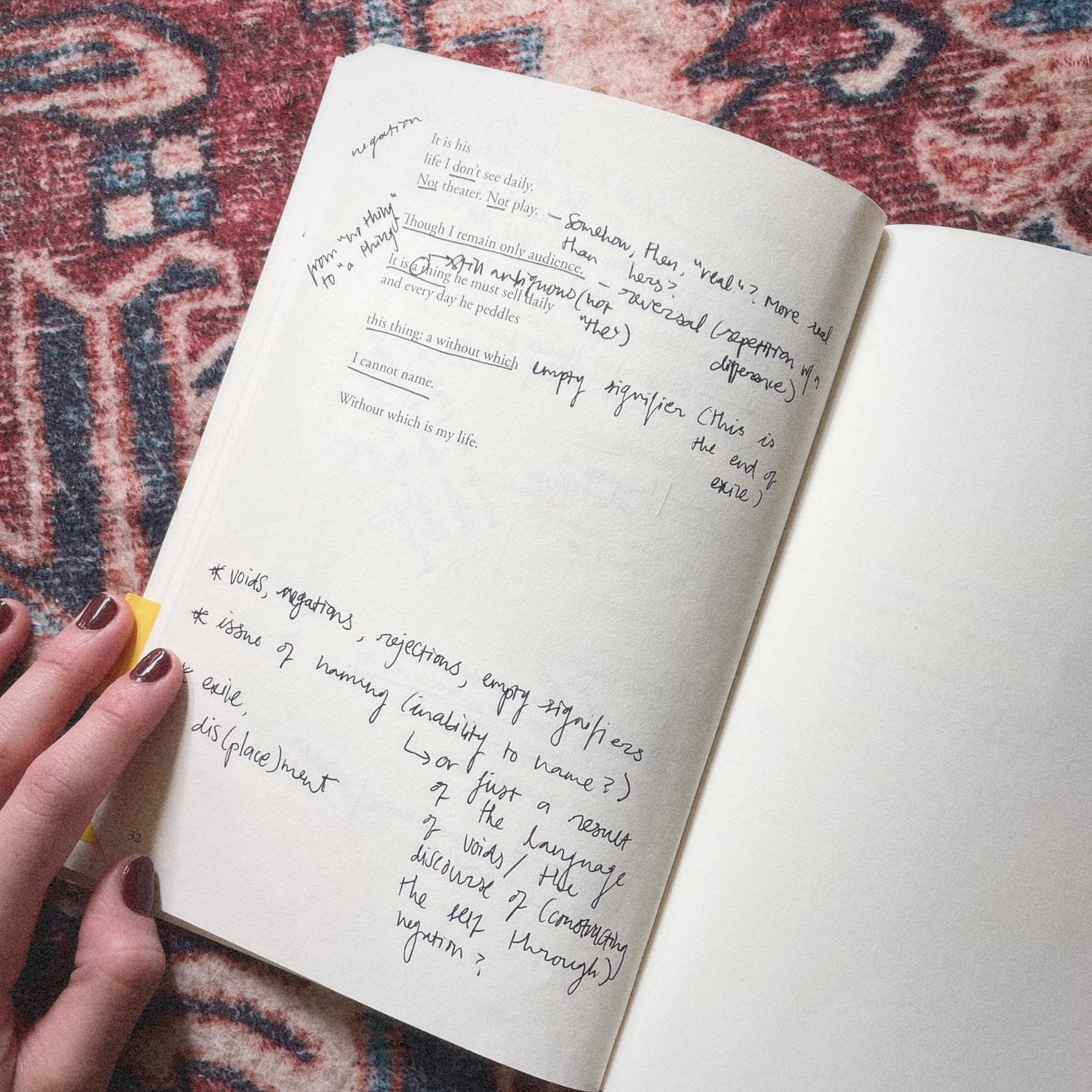

I typically perform these close readings in a relatively meticulous way, line by line, and I’ve done my best here to reference each stanza as I go through the poem, but below I’ve also included images of the text from my copy of Customs, which is totally marked up, but which you can use to follow along with me. You can also read the poem here.

Right away, via simile, the speaker identifies herself as one of “the dead.” It’s important to note that the simile — which is an approximation, as opposed to a metaphor, which is a direct correspondence — acknowledges a certain kind of death while still maintaining and asserting a materiality to the body or to presence of the speaker, the one who comes “without.” The speaker comes without “the city” she is “of” (and here I wonder what it means to be of the city, as opposed to, for example, from the city).

The figure of “the city” here resembles Hélène Cixous’s theorization of the lost / destroyed / desired city in her lecture “Promised Cities.”

Cixous:

“Everything has always been a stage and a theater. This is peculiar to the City: the City is a theater, on whose doorstep the place where the drama, that is to say the theater is played out…”

Sharif:

“To watch play out around me / as theater—”

Throughout the poem, the speaker engages a kind of discourse of negation: to be “without” something (the city), for that something to be missing, like a loss or wound. The city, in this case, is figured as an absence and reinforced by this language of negation. In the fourth stanza, for example, there’s disavowal in every line: “not mine,” “as not,” “as never.”

In the fifth stanza, however, the city is finally named:

“Turning down Shiraz’s streets / it turns out to be such // a faraway thing.”

Naming the city brings the speaker, the poem, and the reader to closer proximity with that which has otherwise been figured through absence and negation, and at the same time, it (re)establishes distance. Even through the proximity or intimacy of walking down the streets of Shiraz (the city she is “without”), it’s still “a faraway thing.” The lost city remains lost. The speaker moves between proximity and distance, but the city nevertheless maintains its position as fundamentally displaced.

“How to say what he is selling,” the speaker wonders. Responding to her own inquiry and attempting to describe what the street vendor is selling, she answers by way of negation:

“it is no thing / this language thought worth naming.”

By “this language,” the speaker means English, the language in which she’s writing. This issue of naming points to a problem of translation, and the inability (or is it a refusal?) to name the “thing” here contrasts the earlier moment of naming the city. The speaker doesn’t have the language to relay or make meaning out of this “thing.”

This moment of non-translation / negation / refusal renders that which the man is selling a “no thing,” creating a linguistic void and rendering the street, and by extension, the city, as an absence and, therefore, lost to the speaker. This can also be understood, then, as an inability to translate the city. This “thing,” which the vendor is selling, since it cannot be translated, is described through a language of negation: “no thing.” The speaker is thus exiled by the inability to make meaning in either one language or the other — a kind of exile within an exile.

This displacement is further emphasized in the following stanzas:

“It is his / life I don’t see daily. / Not theater. Not play. // Though I remain only audience.”

In the first of these two stanzas, the poem continues that language of negation, in that the speaker is describing what she “see[s] daily” by way of absence. In other words, she only describes what she doesn’t see: “his life.” Which, again, she can only explain by way of negation: “Not theater. Not play.”

The second of the two stanzas, however, finally offers a kind of affirmation, a semblance of something to fill in the gap. The only thing the speaker names here is herself as “audience.” The speaker thus acknowledges her role as an outsider, an audience member, an observer — thereby also acknowledging the distance between herself, the man, and the city.

The speaker “remain[s] only audience,” as if she’s is in an entirely different realm from the man on the street. The man’s life (“Not theater. Not play.”) doesn’t participate in this dynamic of observer and observed, which leaves the relation one-sided, incomplete, untranslatable. They are on the same street, but they may as well be on different planets. They are “of” the same city (Shiraz), but only one of them (the speaker) is “without” it. The speaker is construed as a specter here, haunting the city, watching everyday life go by, a mere observer in the audience.

As the poem continues, the speaker gets a bit more specific about the “thing” the man on the street is selling. She writes, “It is a thing he must sell daily,” shifting from negation (“it is no thing”) to vague identification (“a thing”). This shift from negation to indefinite article reflects a growing specification of the object, which nevertheless retains its fundamental ambiguity. The speaker doesn’t refer to the object using a definite article (for instance, the) because she can’t access this level of specificity.

In the following stanza, we get another shift: this time, from “a thing” to “this thing.” The deictic term, “this,” seemingly indicates a more specific referent, but again, what follows is only more negation:

“a without which / I cannot name.”

As soon as it seems the speaker might finally arrive at some sort of specificity, it’s once again negated / refused / left untranslated.

The seventh stanza links up with the first stanza through the word “without.” In the first stanza, “without” modifies the condition of the city to the speaker. It’s not only the city she is “of,” but it’s also the city she is “without.” In the seventh stanza, after the city is named, she expands on this condition of loss: “A without which / I have learned to be.” The speaker uses the term “without” as a kind of alternative nomenclature — a linguistic void — to the city as proper noun, Shiraz.

The speaker invokes this “without which” again in both the antepenultimate stanza and the final stanza. In the former, it designates the object the vendor is selling on the street. Here the deictic (“this”) finally approximates some specificity to the object, in that “this thing” is followed by a colon, which ostensibly signifies specificity. We expect the colon to be followed by some information indicating some semblance of exactitude expanding on what precedes said colon. What follows, however, is more absence, another omission, “a without which // I cannot name.” The empty signifier is woven through the entire poem from start to finish.

The very last line of the poem seems to be yet another attempt at naming the loss, as Sharif writes:

“Without which is my life.”

At this point, the omission, the “without which,” is the absent presence signifying the street vendor’s product, which the speaker cannot name. And because she cannot name it, it remains an empty signifier: a “without.” However, that which the speaker is “without” is (paradoxically) her own life.

Perhaps the speaker is saying, then, that this “without” — either as an omission or as a placeholder — may never be imbued with meaning, that it must necessarily remain lost, because it’s precisely this absence that comes to signify one’s presence in exile. To accept the empty signifier is to accept the displacement. To end exile, one must resist the temptation to fill the empty signifier. The end of exile is the centering of that which must remain untranslatable, lost, empty — either as a placeholder or as sheer absence.

As I mention at the top of this post, this is a raw close reading of the poem without much reference to theoretical frameworks to help nuance, develop, and refine the close reading. If my interpretation makes you think of something (or someone) you think I should read, please feel free to drop it in the comments!

This line by line analysis is very cool. When I was in grad school, I wrote my thesis using interpretative phenomenological analysis and the raw data collection was very similar!! Im excited to see what you do with your interpretation!