‘“I wish I could love someone so much that I would die from it.’” —Lucy, Jamaica Kincaid

I have officially decided that Jamaica Kincaid’s novel Lucy is one of the most beautiful books I have ever read. This is my formal declaration.

I had read and engaged with bits and pieces of Kincaid’s work before, but nothing substantial — and honestly, most of what I knew about her came from reading around her work. But this year I finally read her properly for the first time, as her novel Lucy is on the syllabus for a class I was a TA for this quarter. I had the pleasure of discussing the novel a bit with some of my students in section and office hours, but it wasn’t enough, and I couldn’t get it out of my head, so I wrote about it.

This essay is about the role of the visitor in Lucy, the relationship between Lucy and her mother, and the use of photography in the novel; and it represents only a fraction of my thoughts and feelings about the book, but I hope it moves you to want to experience for yourself what I mean.

Jamaica Kincaid’s novel Lucy tracks the development of our eponymous protagonist who leaves home in the West Indies to work as an au pair in the states for a married couple, Mariah and Lewis, and their children. Although it takes some time for Lucy to adjust to her new life in Lewis and Mariah’s home, which represents a microcosm of the broader American culture Lucy’s just stepped into, she’s chosen to be there. Lucy is stimulated by the vast possibility her future now encompasses in this new place. And she’s not particularly nostalgic for home. In fact, she quite resents her home and all that it represents for her: confinement, regression, and submission — to her mother in particular, whose beliefs about how to be a woman clash with Lucy’s desires. However, she struggles to navigate between who she was back home and who she is or could or wants to be now. And since she’s titilated by the vast possibility of her future, Lucy fights to detach herself completely from her mother/land. It isn’t enough to physically escape home. She needs to free her mind and body from the remnants of the mother/land’s constraints, too.

When Lucy first arrives, Lewis and Mariah call her The Visitor, which she doesn’t quite understand. Lucy certainly doesn’t feel like she’s just a visitor, seeing as she lives (for the foreseeable future) with Mariah and Lewis in their home and spends all of her time with them and their children. Mariah and Lewis nevertheless relegate Lucy to the periphery, labelling her The Visitor. But the role doesn’t resonate. Lucy doesn’t feel like a visitor. She feels like she’s a significant part of things — and technically, she is: the entire family depends on her for help with childcare and housework. While Lewis and Mariah orient her toward an itinerant position, Lucy refuses it. She has no intention of being a temporary visitor. She has every intention of detaching herself from her home and (re)attaching herself to this new place. And she has every intention of staying far away from that previous life of hers. For Lucy, going back home — to her mother — isn’t an option, but Mariah and Lewis treat Lucy like she’s a member of “a group in transit,” as Edwidge Danticat writes:

“We, immigrant blacks and African Americans alike, were treated by those who housed us, and were in charge of schooling us, as though we were members of a group in transit.” —Danticat, “Message to My Daughters,” from The Fire This Time (ed. Jesmyn Ward)

The Visitor

One night at dinner with the family, Lucy shares a slightly odd dream she had about Lewis (involving being naked and running around the house, among other things). In response (and to offset the discomfort at the table), Mariah cracks a joke: “Dr. Freud for Visitor.” Lewis laughs to himself, but Lucy doesn’t get it. She doesn’t know who Freud was, doesn’t share the Western frame of reference. And it’s this same frame of reference that drives Lewis and Mariah’s misinterpretation of Lucy’s dream. By sharing her dream with them, Lucy meant to communicate that she had “taken them in, because only people who were very important to me had ever shown up in my dreams.” Lucy shares her dream with the family to try and get them to understand that she’s not on the periphery. By sharing her dream, she seems to be saying Look, look at me, how could I be just a visitor when I am telling you that I had a dream about you, that in the deepest part of my thoughts, you were there. Lucy is trying to refuse the role of Visitor. She wants to be seen as a permanent fixture in their landscape.

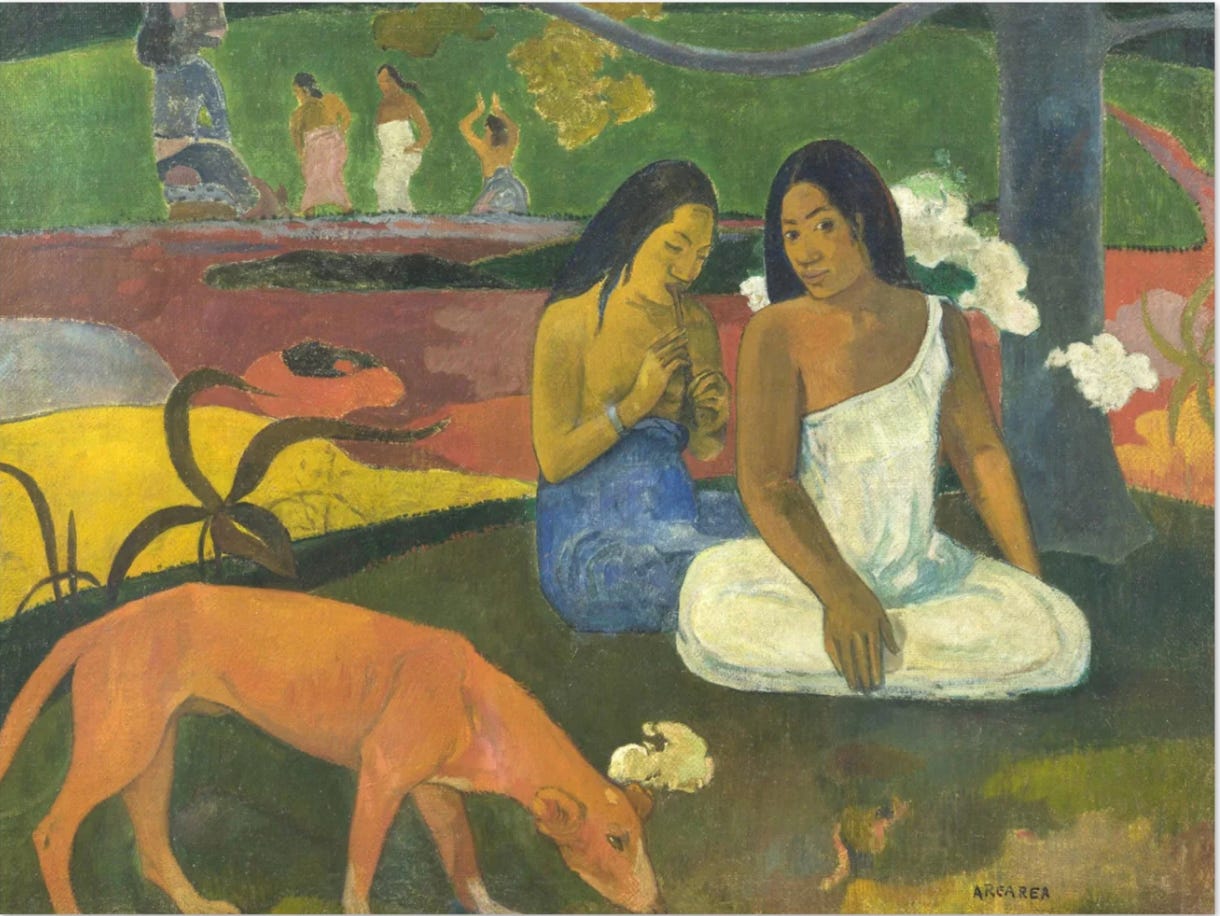

Eventually, Lucy settles in and comes to enjoy her new life in the States with Lewis and Mariah and the children. Although she experiences moments of disillusionment, she also experiences moments of “great happiness” and the “desire to imagine [her] own future.” She’s even grown accustomed to the comforts of her en suite at Lewis and Mariah’s, underestimating what she romanticized only months earlier. She also discovers and becomes enamored with the work of French painter Paul Gauguin after Mariah takes Lucy to a museum to see (what’s sub-textually assumed to be) Gauguin’s paintings of Tahitian islanders, insinuating the possibility that Lucy might identify with them. On the contrary, Lucy ends up identifying with Gauguin:

“I identified with the yearnings of this man; I understood finding the place you are born in an unbearable prison…” —Kincaid, Lucy

This reminds me of one of my favorite moments from Aria Aber’s Good Girl, when Nila discovers and becomes enamored with Kafka’s Metamorphosis in a college class and over-identifies with Gregor Samsa, the bug:

“Who would understand the perils of a man trapped in his childhood room in human form more than an Afghan girl trying to live?” —Aber, Good Girl

The “unbearable prison” Lucy refers to in Lucy is the bulletproof bond between her and her mother. Lucy’s relationship with her mother, like all good mother-daughter relationships, is characterized by both fear and love. At one point in the book, Lucy misses her period and instantly thinks of her mother instructing her to drink a potion with certain herbs in order to induce her period, but her mother never tells her how or why she might miss a menstrual cycle. Lucy claims that her and her mother both knew the cause of a missed period, but they never acknowledged it. They “presented to each other a face of innocence and politeness” instead. Nevertheless, when Lucy misses her period, she both tenderly and reservedly remembers this memory. However, she also starts to panic slightly. She can’t remember which herbs her mother instructed her to pick and boil, but she can’t bring herself to writer to her mother and ask her for them. Lucy can’t tell her mother that she’s having unprotected sex out of wedlock not only because she’s actively avoiding her mother and ignoring all the letters she’s sent her, but also because of the sort of politics of respectability between the two of them, the same force between them that prevented her mother to speak about why exactly a woman would miss her period. Lucy says she’d “rather die than let her [mother] see [her] in such a vulnerable position—unmarried and with child.”

Her Mother

Lucy’s arrival to the States isn’t her first attempt to flee her mother’s rule. She admits that she’d made a “few feeble attempts” before to “draw a line” between her and her mother, but “her reply always was ‘You can run away, but you cannot escape the fact that I am your mother, my blood runs in you, I carried you for nine months inside me.’ How else was I to take such a statement but as a sentence for life in prison whose bars were stronger than any iron imaginable?”

On the one hand, it seems perfectly clear why Lucy interprets her mother’s statement as “a sentence for life in prison,” even if it seems hyperbolic. It’s absolutely true that there’s nothing Lucy can do to escape the fact that her mother is her mother, that her blood runs through her, that she was Lucy’s first home. It is a kind of life sentence. Ironically, this is perhaps the closest Lucy’s ever gotten to being a kind of permanent fixture in someone’s landscape, as opposed to being the Visitor.

On the other hand, her mother’s statement is literally a sentence. Kincaid might be playing on the double meaning of sentence here: as both a punishment and also a string of words. Her mother’s sentence is not only a punishment but also a statement — potentially even a declaration of love. Lucy seems to be caught in between these two meanings. She’s terrified of both her mother’s punishment and her mother’s love. The love scares her because of how binding, unconditional, and intense it is; and because of how much Lucy longs for a love like that: the kind of love that completely subsumes one into the other.

This kind of love-hate relationship is further symbolized by the bounty of (unopened) letters Lucy has from her mother. Lucy lets the letters pile up and never opens them, never writes back. Her silence is intentional. She wants to hurt her mother, like “one lover rejecting another.” If she can’t face up to her mother’s sentences — neither her punishments nor her declarations of love — then naturally she can’t read her mother’s letters, which likely contain more sentences to a life of imprisonment. Or worse: the letters may even contain declarations of love.

“I knew that if I read only one, I would die from longing for her.” —Kincaid, Lucy

Although she never opens them, Lucy clings to her mother’s letters so hard that they “became part of [her] body.” Echoes of her mother’s declaration resound here: the two share a body again, like when Lucy was in her mother’s belly, but this time Lucy’s mother (by extension of her letters) is part of Lucy’s body.

“I was not like my mother,” Lucy reveals, “I was my mother.” And her life is her mother’s: “I could see the present take a shape — the shape of my past. My past was my mother…” If her present is taking the shape of her past — which is to say, the shape of her mother — then Lucy’s life is not really hers. It’s her mothers; or at least, it’s the shape of her mother’s. No matter how far away she is from her mother/land, she can’t seem to escape the bind. Lucy tries to find her own way and write her own story, but the blurred boundary between herself and her mother renders her a visitor in her own life.

Photography

After Mariah takes Lucy to the museum, she buys her a camera, which inspires Lucy to start taking pictures. Photography then becomes a medium through which Lucy regains control over her narrative. Kincaid might be playing with another double meaning here, in that the camera presents a new lens through which Lucy can view the world — a lens both literally and figuratively. Lucy takes black-and-white photographs of Mariah preparing dinner and the children making funny faces, but she doesn’t take any photographs of herself. All around the walls of her room she has her pictures up, and one quiet night, after the children go to sleep, she looks around her room and admires her work. Among the photographs of Mariah and the children, Lucy describes one picture that signals a trace of herself, her own person: “a picture of my dresser top with my dirty panties and lipstick, an unused sanitary napkin, and an open pocketbook scattered about.” Panties, lipstick, napkin, pocketbook. The closest Lucy gets to a self-portrait.

Each photograph represents a moment in time from Lucy’s new life away from home and away from her mother. Taken together, the photographs work to create a kind of alternative narrative, one that portrays Lucy and her life in a light she’s chosen for herself. As the picture of the used panties and unused napkin signifies, photography enables Lucy to construct herself beyond the constraints of her mother’s notions of womanhood and respectability. The camera lens gives Lucy a lens — and a newfound sense of belonging behind the lens.

In On Photography, Susan Sontag uses a metaphor of the camera as a passport to signal photography’s capacity to function as a mode of belonging:

“The camera is a kind of passport that annihilates moral boundaries and social inhibitions, freeing the photographer from any responsibility toward the people photographed. The whole point of photographing people is that you are not intervening in their lives, only visiting them.” —Sontag, On Photography

Having a passport only signals a certain kind of (incomplete) belonging: one that “annihilates moral boundaries” between the photographer and the photographed — something Kincaid herself has written about in the context of tourism in A Small Place (1988) — such that the photographer is “only visiting them.” Photography, then, still renders Lucy a visitor.

While photography crucially functions as a means of not only reclaiming her narrative but also recreating it in a tangible, visual way, it does so without real recourse to Lucy’s search for a stable identity. If, according to Sontag, one can only be a visitor in another’s life as a photographer, then Lucy’s use of photography — as a potentially liberatory mode of creative expression — fails. It fails because, behind the camera, Lucy simply reproduces the role she’s attempting to refute: that of Visitor.

Lucy eventually leaves her post at Lewis and Mariah’s to live with her friend Peggy in the city, working as a secretary for a photographer who lets her use his dark room to develop her film when he’s not using it. Lucy “continued to take photographs, but [she] had no idea why.”

Writing

Before Lucy leaves for the city, Mariah gives her a parting gift: a journal from Italy with a red leather cover and blank white pages. Alone one night in her new apartment in the city, Lucy notices the red journal next to a fountain pen on her bedside table. She takes the pen, opens the journal, and writes her full name at the top of the page. Moving beyond the panties, lipstick, and napkin, we get a different kind of self-portrait here. A more accurate one, closer to reality, in that Lucy cannot displace herself in her own name.

Then, in a surprising and seemingly spontaneous confessional moment, she writes in her journal:

“‘I wish I could love someone so much that I would die from it.’” —Kincaid, Lucy

Recall Lucy’s avoidance from earlier: she refuses to open her mother’s letter because she feels she would “die from longing” for her mother if she read even one of her letters. The irony here is that she simultaneously wishes she could love someone so much that she dies from it but forgets that this is the very thing she’s been fighting for most of the novel. It’s the very reason why she refuses to read her mother’s letters. As Lucy looks at the sentence she’s just written, she feels great shame and begins weeping uncontrollably.

Kincaid dramatizes this scene of writing, once again playing on the double meaning of sentence in this final scene of the text. The sentence moves Lucy to tears. It, too, is a kind of life sentence, like her mother’s: Lucy feels doomed to spend her whole life wishing she could love someone so much that she’d die from it. And she feels shame because she’s spent all her life rejecting this very form of love from her mother.

Photography doesn’t seem to rid Lucy of playing the part of Visitor, despite the camera’s ability to literally and figuratively give Lucy a new lens on her own life. Writing, however, seems to get Lucy closer to fully inhabiting herself and her life. Lucy’s confession of desire — her wish to love so hard she’d die from it — is materialized through writing. But before she writes that sentence, she writes her name at the top of the page. That the act of writing her name precedes the confessional moment suggests that writing in particular contains a kind of transformative potential that photography, as an alternative medium, couldn’t enact for Lucy. Lucy’s approximation of a self-portrait (through the picture of the panties, lipstick, and napkin) displaces the self, while writing her name unavoidably centers the self.

I’m reminded of Deborah A. Miranda’s Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir here — in particular the chapter titled “Petroglyphs” — where she also writes about writing her name:

“It was as if, when I wrote those letters, made a written record of my self, my name, my existence, those letters grew roots and plowed down through that Formica countertop, into the wooden floor, beams, and concrete foundation of the cabin, deep into the heart of the Tehachapi Mountains themselves. I had staked myself to this world. I had created a space for myself.” —Miranda, Bad Indians

Lucy writes those two lines — her name and the confession — and can’t continue. But maybe it’s enough to nudge her forward toward finally staking herself to this world and to herself. Writing gives Lucy a certain kind of access to herself that photography doesn’t. Lucy can write herself into a place of belonging, where she feels like a resident in her own life, rather than a visitor in someone else’s.